How many participants do you need for a usability study?

Do you need to test more than 5 users?

I’m back! Apologies for the silence. I’ve been recovering from a bout of labyrinthitis and I wasn’t able to do much for a whole month. Nowhere near normal yet but I can work and use a laptop again! Hurrah!

So people often ask me; how many people do we need for our usability study?

This question is a source of a lot of debate between UX researchers and stakeholders. Our goal as UX professionals is to balance reliability with business goals and other limitations (e.g. budget or time). This means that we should be able to identify the risks and implications of testing with different sample sizes and recommend a group size that is optimal for each study…

Often UX researchers accept popular advice on this matter without being aware of where and how this advice should be applied. An example of this is Nielsen’s advice that “a usability study with five participants will discover over 80% of the problems with an interface”. This well-known advice is based on studies by Virzi (1992) and Nielsen (1993).

According to Macefield (2009), that’s how they came to this conclusion:

“100 groups of five participants were used to discover problems with an interface. The study did indeed find that the mean percentage of problems discovered across all 100 groups was about 85%. However, this figure has 95% confidence level and a margin of error of ±18.5%. This means that for any one particular group of five there is a 95% chance that the percentage of problems discovered will be in the range of 66.5%-100% and, indeed, some groups of five did identify (virtually) all of the problems; however, one group of five discovered only 55% of the problems.”

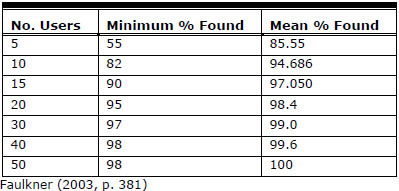

More recently, Faulkner (2003) attempted to answer the same question using a statistical sampling approach. She found that, on average, Nielsen's prediction is right. Testing five users over 100 simulated tests revealed an average of 85% of the usability problems identified with the larger group. When looking at the data closely, however, the range of usability problems identified by groups of 5 participants ranged from almost 100% to only 55% (similar to earlier studies). What does this mean for UX researchers? When we rely on only 5 users we run the risk of missing almost half of the usability issues.

Looking back at Faulkner’s results, we can see that increasing the number of participants can solve this issue and improve the reliability of our findings. More specifically, using 10 participants can uncover 95% of the problems on average (range 82% to 100%1). Increasing the number to 15 can identify 97% of the problems on average (range 90% to 100%).

Of course, it’s not always possible to recruit more than 5 participants and we’re not always looking to uncover all usability issues at once! So what should we do?

Like in many things in UX research, there’s no one size fits all approach we can adopt! The answer depends on a number of factors and should be evaluated before each study. Some of the factors to consider are the following:

the impact of the study: what’s at stake if you don’t uncover as many usability issues as you can? Stakes are higher when you’re testing a system that could cost people’s lives versus a new feature in a shopping app. The bigger the impact, the more participants you should recruit.

the complexity of the product/system being tested: the optimal group size should be influenced by the study’s complexity, with larger numbers of participants being required for more complex studies. The complexity of a study can be evaluated by some of the following criteria; the complexity of the system being tested, the scope and complexity of the task used, the diversity of the participants, etc.

the target user groups of the product: If you’re working on a product that has different types of users, you’ll need to test with participants from all groups to get valid results. For example, if you have two different types of users (e.g. sellers and buyers) you need to recruit a representative sample of users from each group (e.g., 5 sellers and 5 buyers).

the stage in the development cycle: the earlier you are in the development process, the more likely you are to discover severe errors affecting the functionality of the product. As a result, you can start by recruiting smaller samples. As the product becomes more refined and fine-tuned, usability issues are harder to find, requiring larger samples.

the tasks users have to perform: the more complex the tasks, the more users are required. You can get away with smaller sample sizes when asking users to complete simple tasks.

the purpose of the study: The goal of the study can affect how many participants we need to recruit. For example, conducting a usability study for political reasons (e.g., convince stakeholders) requires a small sample (2-3 participants) but if we want to test the usability of a new product a larger sample is required to help us uncover as many issues as possible.

According to a review by Macefield (2009), we can argue that “for most studies related to problem discovery a group size of 3-20 participants is valid, with 5-10 participants being a sensible baseline range, and that the group size should be increased along with the study’s complexity and the criticality of its context”.

Attention: More participants won’t help if the test quality is poor…

Research has shown that the results of usability tests depend considerably on the evaluator (Jacobsen & Hertzum, 2001). For example, using invalid test tasks or not facilitating a session properly. Errors in usability testing are not uncommon — even experienced researchers make them.

As Molich (2010) suggests if we are using poor methodology, the results of the study will be poor irrespective of the participant group size…. Choosing the right methodology and trying to prevent facilitator errors should be a priority.

“almost 100%”. We can never uncover all usability issues

Great article Maria and a common question that many need to consider. I find it surprising that the research is a bit dated, or there hasn't been much addition to the research from Virzi and Nielsen in the early 90's to Macefield in 2009. Do you think there is a knowledge gap or these findings are still true today? (decades since the Virzi and Nielsen research)