Understanding contrast ratio and accessibility

Contrast is the ratio of the luminance (perceived brightness of a colour) of the brightest to the darkest colour that the system can produce. In simpler terms, contrast ratio refers to how bright or dark colours appear on interfaces. It can range from 1 to 21 and is expressed as two numbers separated by a colon (e.g., 7:1). The first number refers to the relative luminance of light colours while the second number refers to the relative luminance of dark colours.

Contrast is not “real”, it is a perception. Contrast sensitivity refers to the ability to detect subtle differences in shading and patterns. Contrast perception changes throughout our lifetime and can be affected by various health issues or medication. Contrast sensitivity can be measured clinically by using a contrast sensitivity chart such as the Pelli-Robson Contrast Sensitivity Chart depicted below. Individuals are asked to read the letters on the chart; the contrast is greater at the top and it becomes lower as it progresses. Scoring is based on the ability to see the letters.

A condition affecting the way we perceive contrast is colour blindness (or else known as colour vision deficiency). Around 1 in 12 men and 1 in 200 women have some degree of colour blindness. This is a topic I have briefly covered previously.

The image above is a plate from the Ishihara test, a test for colour vision deficiency. If you can see the number 74, you probably have normal colour vision (but this is only one part of the test). If you can see 21, you may have a red-green colour vision deficiency. Research has shown that even people with normal colour vision experience a decrease in their contrast perception and colour sensitivity as they age. This means that not all users perceive contrast in the same way.

It can also be influenced by contextual factors such as the context of the nearby colours and other features of a design or image. This makes predicting contrast in designs quite challenging. Looking at the distance or ratio between two colours is not enough.

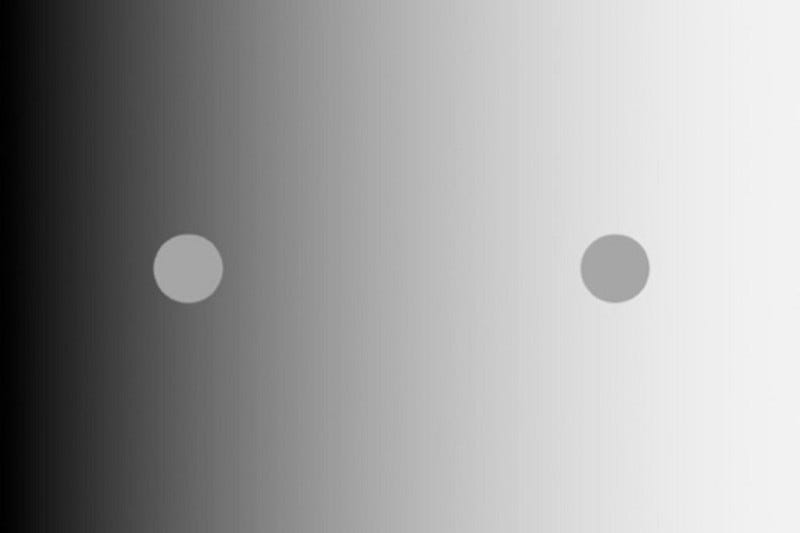

Optical illusions, such as the simultaneous brightness contrast illusion(see figure below) demonstrate how our perception of shades (and colours) changes according to their visual context. In the example below the same coloured object is perceived as lighter or darker grey depending on its background colour.

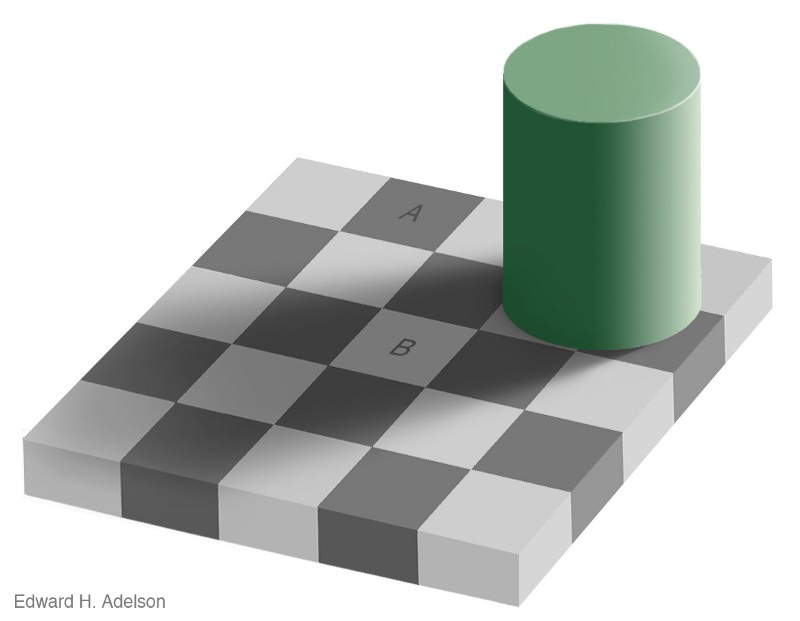

Another example of this is the Checker-Shadow Illusion pictured below. In this illusion even though tile A and tile B are identical, one of them is perceived as lighter than the other. These illusions work because of the way our brain processes information about contrast and shadows. In order to determine the colour of objects, we use relative colour and shading.

Accessibility matters

When it comes to accessibility, the contrast ratio is a concern for how elements appear on devices by default. Even though most devices allow users to adjust brightness levels, contrast isn’t always adjustable.

This means that finding the right contrast for the different elements of a website/app is crucial for visually impaired users (e.g., colour-blind individuals, older users). The WCAG 2.0 guidelines dictate the following:

For normal text (<18, not bold, or <14 if bold): A minimum contrast ratio of 4.5:1 for the visual presentation of both text and images embedded as text is required. More specifically, this criterion applies to text in the page, including placeholder text and text that is shown when a pointer is hovering over an object or when an object has keyboard focus. If any of these are used on a page, the text needs to provide sufficient contrast. The 4.5:1 contrast ratio is intended to address the loss of contrast that users experience if they have low visual acuity, age-related loss of contrast sensitivity, or colour deficiencies.

For large text (18 point, 14 point if bold, and larger font sizes plus images of very large text): WCAG 2.0 requires a 3:1 contrast ratio. Text that is larger and has wider character strokes is easier to read at lower contrast. The contrast requirement for larger text is therefore lower.

Text that is decorative and conveys no information is excluded. For example, random words that don’t add information to the content of a page but are used for decorative purposes do not need to meet this criterion. No contrast requirements exist for logotypes and incidental text, which is text that has no context to the product’s core purpose. Some examples of this are inactive user interface components (components not available for user interaction), text for decoration, and text that is part of mainly visual content.

The contrast ratio suggestions discussed above were initially aimed at text but similar issues occur for content presented in non-text based forms, such as charts, graphs, diagrams. Content presented in this manner should also have good contrast to ensure accessibility and follow the same guidelines.

A contrast ratio of 3:1 is the minimum level recommended by [ISO-9241–3] and [ANSI-HFES-100–1988] for standard text and vision. WCAG 2.0 recommended a 4.5:1 ratio in order to account for the loss in contrast that results from moderately low visual acuity, congenital or acquired colour deficiencies, or the loss of contrast sensitivity that typically accompanies ageing.

To achieve level AAA, a higher contrast ratio of 7:1 is required. This is to compensate for the loss in contrast sensitivity usually experienced by users with vision loss equivalent to approximately 20/80 vision. People with more severe vision loss usually rely on assistive technologies to access content.

However, not all groups benefit from increased contrast. For example, individuals with autism can find lower contrast ratios easier to process and higher contrast ratios can potentially be distracting. This is something we need to consider when designing for specific groups.

A number of tools exist that allow us to test whether our designs comply with accessibility guidelines. A list of various tools can be found here. However, following WCAG guidelines alone is not always enough. It is always important to test our designs with actual users whenever possible.

An example from Slack

Slack, one of the most widely used workplace team messenger platforms, reduced the colours from 130 to 18 in order to meet accessibility standards. Both designers and engineers benefited from this change as it was easier to manage and it allowed them to spend more time working on other problems.

With this small set of colours, the team was able to focus on the most pressing accessibility issue they had, which was the low contrast elements in the interface. Hubert Florin, one of the UX designers at Slack, wrote:

A more contrasted interface is easier to use for everyone, not just people with vision impairments. But the transition to a more contrasted interface can be difficult at times. Whenever we would make a portion of the interface darker to meet accessibility standards, the immediate feedback was that it was too dark, too polarizing. People are used to the existing interface and don’t even realize the effort they have to make to use it. But after a few days, when the dust settles and they get use to the new colors, if you show them how it was before, they tend to have the exact opposite reaction. Suddenly they realize that they always had to make an effort to see the interface, even though their vision was completely fine.

An example of the old and new interfaces of the platform can be seen below.

Even though people were initially resistant to change, in the end making the interface more contrasted increased the usability of the platform for everyone, not just for individuals with accessibility needs.

“Accessibility is not a constraint: It is a design philosophy that encourages you to make better choices for your users, and helps you focus on what really matters. Simplicity will always be the most difficult target to reach in a design, and accessibility can be one of the best tools to get you there.” — Hubert Florin