The Olympic Mindset: Applying Less-Is-Better and Counterfactual Thinking to UX

Lessons from Olympic Medalists

It's been a fascinating summer so far for anyone into sports! The Olympics just came to an end, and apart from generating multiple memes, they provided the inspiration for this post!

Did you notice something peculiar during the medal ceremonies? While the gold winners are understandably elated and the bronze medalists often seem genuinely thrilled, the silver medalists frequently appear... well, less than enthused. You might wonder why that is. For most of us a second place in a competition like the Olympics is an incredible achievement!

This phenomenon actually has a name in psychology: the less-is-better effect, a cognitive bias where people sometimes prefer a smaller or lesser outcome over a larger or better one. This effect is closely related to counterfactual thinking — our tendency to imagine alternatives to events that have already occurred. In this article, we'll explore the less-is-better effect and counterfactual thinking, and discuss potential implications for user experience (UX).

Counterfactual Thinking

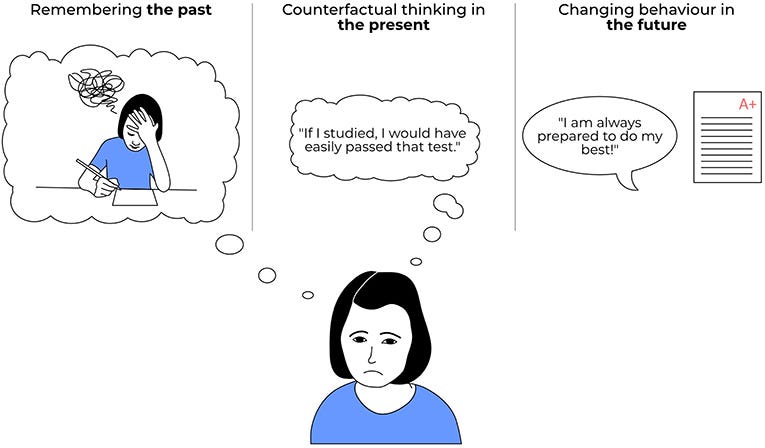

Counterfactual thoughts are mental representations of alternatives to past events, actions, or states (Roese, 1997) — imagining how things could have been different in the past. These "what if" and "if only" thoughts play an important role in how we evaluate outcomes and experience emotions. There are two types of counterfactuals:

Upward counterfactuals: Imagining how things could have been better.

Downward counterfactuals: Imagining how things could have been worse.

Counterfactual thinking can serve various functions including:

Preparative: Learning from past experiences to improve future outcomes

Affective: Regulating emotions (e.g., feeling relief by engaging in downward counterfactuals)

The Olympic Medal Study: Less-Is-Better Effect in Action

A seminal study by Medvec, Madey, and Gilovich's (1995) on Olympic medallists showed how counterfactual thinking can lead to the less-is-better effect. By standing the reactions of medallists they found that:

Bronze medallists appeared happier than silver medallists, both immediately after their events and on the medal stand.

Silver medallists' thoughts focused more on "I almost" (won gold), while bronze medallists' thoughts centred on "at least I" (won a medal).

This pattern was consistent across different methods: analysis of TV coverage, evaluation of interviews, and direct questioning of athletes.

The researchers attributed these results to the different counterfactual alternatives most salient to each group. Upward counterfactual (comparing to gold) for silver medallists and downward counterfactual (comparing to no medal) for bronze medalists.

Another classic demonstration of the effect comes from Christopher Hsee's ice cream study (1998). Participants were asked about two scenarios: an ice cream vendor selling 8oz of ice cream in a 10 oz cup and a vendor selling 7oz of ice cream in a 5oz cup. Hsee found that when evaluated separately participants were willing to pay more for the smaller amount of ice cream in the overfilled small cup. Believing that the vendor was giving more ice cream than he was supposed to, since it was 7 oz in a 5 oz cup, made people feel like they were getting a good deal. However, when both options were presented together, participants had more information to make a decision and preferred the larger amount of ice cream in the underfilled large cup.

Both these studies highlight how context and framing can lead to seemingly irrational preferences when options are evaluated in isolation.

Research has identified the following key aspects for the less-is-better effect:

Isolated vs. joint evaluation: The effect is most prominent when options are evaluated separately rather than side-by-side.

Norm theory: When evaluating an option in isolation, people tend to compare it to other objects in the same category, rather than to all possible alternatives.

Preference reversal: When options are initially presented separately and then presented together, people often reverse their initial preferences.

Framing: How information is presented significantly impacts our perception and valuation of choices.

Examples of Counterfactual Thinking

Counterfactual thinking isn't limited to sports and consumer choices. Kahneman and Tversky (1982), in their discussion of the "simulation heuristic," demonstrated that near misses often lead to stronger emotional reactions. They used an example of two travellers missing their flights: one by 5 minutes and another by 30 minutes. They proposed that the person who missed the flight by 5 minutes would likely feel worse because it's easier to imagine scenarios where they could have made the flight.

This concept of how easily we can imagine alternative outcomes is closely related to the idea of "mutability" in counterfactual thinking. Mutability refers to the ease with which an aspect of a situation can be mentally altered or "mutated" to create a different outcome. Building on Kahneman and Tversky's work, Byrne (2002) explored how the mutability of different aspects of a scenario influences the counterfactual thoughts people generate.

For example, in the case of the missed flights discussed earlier, arriving at the airport 5 minutes earlier is more mutable (easier to imagine changing) than arriving 30 minutes earlier. This higher mutability makes it easier to generate counterfactual thoughts, leading to stronger emotional reactions. Byrne's research showed that people tend to focus on highly mutable aspects of a situation when constructing counterfactuals, such as actions rather than inactions, or exceptional rather than routine events.

While much of the research focuses on immediate reactions, Gilovich and Medvec (1994) discovered an intriguing temporal aspect to counterfactual thinking. They found that regrets of inaction (things we didn't do) tend to increase over time, while regrets of action (things we did do) decrease. This temporal pattern adds another layer of complexity to how counterfactual thoughts influence our long-term satisfaction and decision-making.

Lastly, it's important to note that even though counterfactual thinking can sometimes lead to negative feelings, it can also have a positive function. Markman et al. (1993) showed that upward counterfactuals (imagining how things could have been better) can have beneficial effects despite sometimes causing short-term negative emotions.

In their study, participants who engaged in upward counterfactual thinking after a disappointing performance on an anagram task showed improved performance on a subsequent task. The researchers proposed that by imagining better possible outcomes, individuals identified ways they could have performed better. As a result, this process prepares people for future situations by helping them learn from experience and adjust their behaviour. Even though the immediate emotional impact might be negative, the long-term behavioural outcome can be positive.

Implications for UX

I have to admit that even though I’ve been familiar with the effect long before getting into UX, I hadn’t previously considered its relevance to it. Working on this article made me consider some potential implications for UX:

Product comparisons: Be mindful of how product options are presented. Offering side-by-side comparisons can lead to different decision-making than presenting options separately. For example, a pricing page that allows users to compare different subscription tiers directly, rather than viewing each tier on a separate page. This gives users more distribution information to make an informed choice.

Feature presentation: When showcasing product features, consider how they're framed. A feature that seems impressive in isolation might be less appealing when compared directly with alternatives. For example, Instead of listing all features at once, gradually introduce features throughout the user journey, allowing users to appreciate each one in context.

Framing value: Frame your product's value in relation to category norms. For example, a productivity app could highlight how it offers more features than the average app in its category, even if it has fewer features than some premium competitors.

User testing: When conducting user research, be aware that presenting options in isolation vs. jointly can significantly affect user preferences. For example, conduct both isolated and comparative usability tests to get a comprehensive understanding of how users perceive your product.

Pricing strategies: Leverage the effect in pricing strategies, especially for tiered services. Example: A streaming service could offer a basic plan that seems generous for its category, even if more comprehensive plans are available.

Marketing approaches: In marketing materials, consider presenting your product both in isolation and in comparison to competitors. Example: Create landing pages that showcase your product's strengths individually, but also provide comparison charts for those doing more research.

Progress and achievement systems: Markman et al. (1993) showed that while upward counterfactuals can sometimes lead to negative feelings, downward counterfactuals can have an immediate positive effect on satisfaction. UX designers could leverage this by creating systems that encourage users to generate positive downward counterfactuals. For example, a language learning app could emphasise streak maintenance and personal bests, rather than highlighting narrowly missed daily goals.

Feedback mechanisms: Byrne's (2002) concept of mutability suggests that the ease of mentally altering an event affects the strength of counterfactual thoughts and resulting emotions. We could frame feedback to focus on less mutable aspects of performance, reducing the ease of generating upward counterfactuals. An educational app, for instance, could congratulate users on mastering specific skills (less mutable) rather than pointing out how close they are to the next level (more mutable).

Long-term engagement strategies: Markman et al.'s (1993) finding that upward counterfactuals can serve a preparative function for future performance, despite short-term negative feelings, can inform engagement strategies. UX designers could create features that channel short-term frustrations into long-term learning and improvement. A fitness app could provide detailed breakdowns of narrowly missed goals, coupled with specific, actionable tips for improvement in the next session.

Onboarding and user journeys: Design user journeys with distinct, achievable milestones rather than a continuous scale of progress. This can help users feel a sense of accomplishment at each stage rather than focusing on what they haven't yet achieved. For example, a language learning app could celebrate the completion of each lesson or unit, rather than constantly showing the user how far they are from full fluency.

Error recovery and customer service: Kahneman and Tversky's (1982) simulation heuristic suggests that near misses can be more frustrating than clear misses. When designing for service failures or errors, providing clear alternatives that encourage downward counterfactual thinking could be beneficial. If a user misses a delivery, offering multiple rescheduling options rather than a single alternative allows users to feel they've chosen the best possible outcome given the circumstances.

By incorporating these insights, we can create interfaces and experiences that align with how users naturally evaluate options, potentially leading to higher satisfaction and engagement. However, it's crucial to use these insights ethically, aiming to genuinely improve the user experience rather than manipulate perceptions.

Conclusion

The less-is-better effect is an interesting and not regularly discussed effect that can affect the way users interact with our designs and products. By understanding how users naturally generate "what if" scenarios and how these thoughts impact satisfaction, we can create products, services, and experiences that align with human cognitive tendencies.

Implementing these insights requires a delicate balance. While we want to encourage positive counterfactual thinking and minimise negative comparisons, we also need to maintain user motivation and drive for improvement. Our goal should not be to eliminate all upward counterfactuals, as these can serve important motivational and learning functions, but to create experiences where users feel satisfied with their current state while still being inspired to progress.

Silver medallists' thoughts focused more on "I almost" (won gold).

This is so true. I a 400m race I lost the gold medal by just one step. Silver was great, but I was disappointed I didn't come first when I couldve.