The Dunning-Kruger Effect: Cognitive Bias or Statistical Artefact?

Exploring the Mechanisms and Impact of the Dunning-Kruger Effect

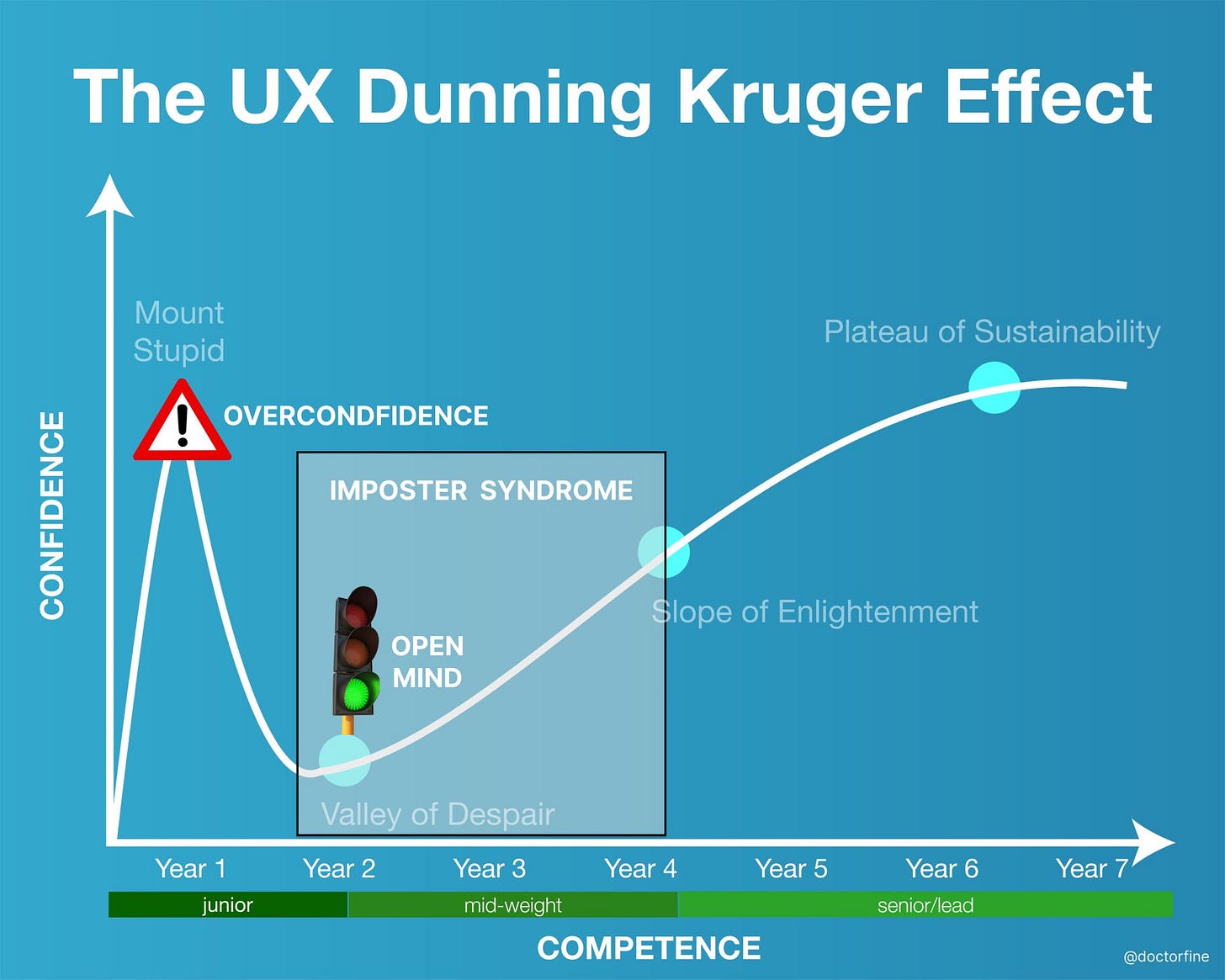

The Dunning-Kruger effect has become a widely discussed cognitive bias among designers and user researchers in recent years. First uncovered in the late 90s, the effect describes the tendency for people with lower ability in a given area to overestimate their own competence. Meanwhile, those with more expertise tend to underestimate their relative skills. This article will explore the nature and impact of this effect in fields ranging from psychology to user experience (UX) design.

The Dunning-Kruger Effect

The effect is named after Cornell psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger, who first documented this cognitive pattern in a 1999 paper published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (Kruger & Dunning, 1999). Across four studies, they gave student participants tests of humour, grammar, and logical reasoning, asking them to estimate their performance both in terms of number of questions answered correctly and their percentile rank compared to peers.

Those scoring in the bottom quartile on the tests consistently overestimated their raw scores and relative performance. In the humor assessment, the bottom quartile estimated on average that they answered 68.6% of questions correctly, compared to their actual mean score of 23.1% correct (Kruger & Dunning, 1999). This reflects a 45.5 percentage point overestimation.

Meanwhile, top performers showed more accurate self-assessment with a slight underestimation bias. The top humour scorers estimated their performance as 72.1% correct when their actual mean score was 86.2% - an underestimation of 14.1 percentage points.

These patterns were attributed to deficits in metacognitive skills. Those with limited ability not only perform poorly, but also lack awareness of their incompetence, inflating judgments of their competence (Dunning et al., 2003). In contrast, highly skilled individuals better judge the ease or difficulty of tasks, underestimating their performance assuming others find tasks as straightforward as they do.

The Effect in Action

This disconnect between competence and metacompetence judgments has been documented across other assessments, including aviation, memory, medical skills, and other areas. It is frequently invoked to explain why the "unskilled and unaware" not only produce low quality output but seem oblivious to their deficiencies.

Understanding the Dunning-Kruger effect is also important for a product development team and UX teams. When creating products, we often rely heavily on user feedback. The Dunning-Kruger effect, however, suggests that those most lacking in competence will provide the least insightful - yet potentially most confident - input. Novices speak loudly, crowding out expert guidance.

The Dunning-Kruger effect has relevance not only in how users assess their own capabilities, but also in how UX professionals view their own skills. Similar to other fields like scientific research or financial analysis, gaps frequently emerge between UX competencies and awareness of competencies.

For example, novice UX designers may lack understanding of fundamental best practices, yet feel very confident in their intuitive design decisions and they believe themselves to have expertise. This overconfidence can persist even in the face of feedback highlighting subpar work. Meanwhile, the most competent designers who stay continually up-to-date on latest trends may underestimate their own performance. Assuming their peers match their efforts and knowledge, they underrate their competencies relative to the field.

The first step in addressing the unconscious bias is acknowledging one's own susceptibility to the Dunning-Kruger effect just like users. This also suggests the importance of embracing a culture of critical feedback, peer review, and growth mindset within UX teams. Opportunities for external assessment like Design Critiques help calibrate both individual's and team's sense of their strengths and weaknesses.

Statistical Artefact or Psychological Phenomenon?

In recent years, criticism has emerged that the pattern observed by Dunning and Kruger requires no biased psychology to produce. Using computer-generated random data, multiple studies have replicated the overestimation and underestimation quartile patterns (Krueger & Mueller, 2002).

This suggests a statistical artefact tied to regression toward the mean and measurement unreliability. Essentially, individuals with extreme scores on any test (high or low) are more likely to score closer to the average on a subsequent test. This can create the illusion of overestimation and underestimation even without any cognitive bias at play. Without any psychological mechanisms, purely mathematical phenomena recreate the effect.

However, supporters argue that while the pattern attenuates when controlling for noise, it does not disappear (Dunning et al., 2003). Moreover, additional analysis shows those in lower quartiles predominantly overestimate themselves, while higher quartile individuals mainly underestimate others (Ehrlinger & Dunning, 2003).

Ongoing inquiries continue to debate the degree to which the effect reflects something meaningful about human judgment versus merely measurement issues. Either way, the core pattern persists, even though its origin remains disputed.

Conclusion

Regardless of precise mechanisms, the presence of gaps between ability and awareness have implications for UX, Product Development, and other fields.

Rather than rely on assumptions about user expertise, conducting research and triangulating our findings is key. Analytics also help separate signal from confident noise.

Acknowledging our own susceptibility to the Dunning-Kruger effect is the first step towards addressing it. Having more opportunities for peer review and continuous feedback can help.