Psychological principles in product design — a closer look at Duolingo

How to use Psychology to improve UX

Since my background is in cognitive psychology, I often consider the role that psychology plays in UX. In this post, I’ll be looking at how certain psychological principles can be applied in product design. In particular, the focus will be the popular language learning app Duolingo and some of the principles it employs to increase user engagement.

Peak-end rule

The peak-end rule is a cognitive bias that affects how people remember past events. It was first described by Daniel Kahneman and colleagues in a 1993 study.

In their experiment they exposed participants to two uncomfortable (but not dangerous) experiences:

A short trial in which they immersed one hand in water at 14 °C (57.2°F) for 60 s

in the long trial, they immersed the other hand at 14 °C for 60 s, then kept the hand in the water 30s longer as the temperature of the water was gradually raised to 15 °C (59°F), still painful but distinctly less so for most people.

Participants were then given a choice to repeat one of the above trials. Contrary to what one would expect, the majority of the participants (80%) chose to repeat the long trial, apparently preferring more pain over less. Why is that? It looks like the slightly less uncomfortable final 30 seconds of the experiment in the long trial changed the way participants perceived the entirety of the long trial. These findings suggest that duration plays a small role in the way we evaluate past negative experiences; such evaluations are often dominated by the discomfort we experience at the worst and at the final moments of episodes. In other words, a small improvement near the end of an experience can shift people’s perception of the entire event.

Duration plays a small role in the way we evaluate past negative experiences; such evaluations are often dominated by the discomfort we experience at the worst and at the final moments of episodes.

The peak-end rule suggests that small changes can have a large impact on the way we experience and remember things. In particular, when designing an experience more attention should be paid to the most intense points of a typical user journey (the “peaks”) and the final moments (the “end”).

Negative peaks of our experience with products are one of the focus points in UX. By making use of appropriate elements at the right time it is possible to transform experiences from pleasant to memorable. This is something Duolingo does really well by including brief playful interactions at the end of each lesson. These interactions create a positive peak and encourage the user to continue their journey.

Presenting the user with a positive stimulus, like the example above, at the end of a successful interaction can ensure users remember the experience in a positive light.

The Von Restorff effect

The Von Restorff effect (also known as isolation effect) is a well-known cognitive phenomenon first described by von Restorff in 1933. According to this effect, if we are presented with multiple similar objects, we are more likely to remember the one that differs from the rest.

In UX we can take advantage of this effect by putting emphasis on elements we want users to interact with and remember. Similarly, we can de-emphasize any aspects we want users to ignore. Instances of the Von Restorff effect are quite common on the Web, particularly in the way service pricing pages are presented.

Duolingo employs this technique to draw the attention of the user toward the most popular offering (and likely the most profitable one for them). By isolating one choice in a field of many (in this case the yearly plan), the design prompts the users to recall and ultimately purchase this particular option.

Another effect displayed in this example from Duolingo is the scarcity bias; the offer appears to be available for a limited time only. People assume (unconsciously) that things that are scarce are also valuable, while things that are abundant are not. By showing that the offer is available only for the next 45 hours, users are more likely to purchase the plan so that they don’t miss a potentially good deal.

Goal gradient effect

The Goal Gradient Effect was first described by Clark Hull in 1932 and it states that as people get closer to a reward, they speed up their behaviour to get to their goal faster. This phenomenon suggests that people are motivated by how much is left to reach their target, not by how far they’ve come.

This effect relates to the endowed progress effect; the idea that if you provide some type of artificial advancement toward a goal, a person will be more motivated to complete the goal. For example, if you’ve ever been to a coffee shop where the barista gave you two stamps instead of one, you’ve been the victim of the endowed progress effect.

Duolingo makes use of both effects described above. A way to encourage users to form habits and practice language learning on a daily basis is by introducing the idea of a streak — using the app for the first time initiates a streak. A quick search shows that maintaining the streak is a big motivator for many users and keeps them using the app. Why is that? Loss aversion is a potential explanation for this effect. People fear losing something more than they desire gaining something of equivalent value. Even though keeping up the streak doesn’t result in any immediate rewards for the user, it increases user engagement and enables habit formation.

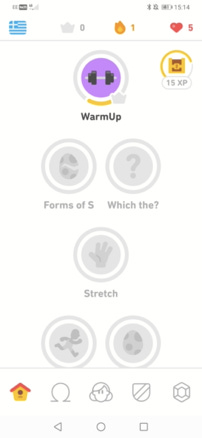

Gamification

Duolingo’s novelty is the gamification of language learning. Games satisfy a broad spectrum of vital psychological needs such as competence and relatedness so adding gamification elements can increase user engagement and lead to a positive user experience.

Chunking

Chunking refers to the process by which the mind divides large pieces of information into smaller units (chunks) that are easier to retain in short-term memory (the capacity to keep a small amount of information in mind in an active, readily available state for a short period of time). Doing this allows us to bypass the limited capacity of our memory, making it more efficient.

This strategy is used extensively by Duolingo; language learning is broken down into bite-size lessons organised by common themes (e.g., family, time, numbers). This makes the process less intimidating and helps users remember the information.

Anthropomorphism

Humans naturally anthropomorphise; we are hard-wired to give animals and inanimate objects (e.g., avatars, mascots) human-like characteristics (motivations, intentions, emotions).

Research has shown that anthropomorphised brands and products can benefit users by fulfilling their need for belongingness (connection) and helping them understand unfamiliar situations (comprehension). Anthropomorphism can also lead to increased empathy.

“There is an universal tendency among mankind to conceive all beings like themselves . . . We find faces in the moon, armies in the clouds” — Hume (1957)

Giving artifacts anthropomorphic appearance and behaviour, affects people’s evaluations of them and their intention to use them. One of my favourite examples of this phenomenon is the case of a little robot from a library in Helsinki that went from reviled to beloved, all because it got a new pair of plastic eyes. You can read the full story here.

Duo, the green owl, has been Duolingo’s mascot since 2011. The unique design of Duo and the way it interacts with users have led to numerous memes… Each iteration of the mascot is becoming increasingly more expressive and human-like, increasing the empathy users feel towards it. Does this translate to an improved user experience?

According to an article from the Verge the latest redesign of Duo made an impact on user experience and led to a small increase in the number of lessons taken and an uptick in subscriptions to Duolingo Plus.

Are there any apps you’d like me to focus on next? Please let me know in the comments.