Improving data quality in online studies

Techniques and strategies for UX Researchers, Market Researchers, and anyone doing online research

Data quality concerns

When conducting studies online (e.g., online surveys, unmoderated usability testing) we can’t see our participants or control their environment when they take part in the study. This generates a number of potential concerns about data quality.

External factors might be affecting their performance: In lab-based studies, researchers ensure participants are in quiet environments with as few distractions as possible and use appropriate equipment. In online studies, however, this is not possible. Participants could be taking part in a study while being in a noisy, distracting environment, or while multitasking. For example, they could fill in a survey while watching a TV show. This could have a detrimental effect on task performance. It is also possible that participants have access to low-quality hardware (e.g., slow internet connections, smaller screens, have no audio, etc).

It is harder to verify the identity of the participant: Even though we can use screeners to filter out certain participants, in online studies, it is hard to know whether participants are who they say they are. For example, they could be lying about their age, gender, background, or other demographic information. This can be especially problematic in cases where participants are given rewards or get paid for their time.

Engagement levels might be lower: Research has shown that approximately 10%-12% of participants can be “identified as careless responders” and don’t pay sufficient attention to some parts of online tasks (Meade & Craig, 2012). This could lead to noisy data.

Participants could be cheating: Two main reasons have been identified to explain why participants might cheat in an online survey (Howell, 2021): Impression management (the process by which individuals control how they are perceived by others) and self-deceptive enhancement (unconscious tendency to give overly positive reports about oneself and reluctance to admit to personal limitations). This leads to participants using external aids when they’re not supposed to (e.g., Googling an answer) or not being honest in a survey.

Why is this a problem?

Research has shown that even a small number of careless responders can affect the results of a study. According to Huang et al. (2015, p.9) “the presence of 10% (and even 5%) … can cause spurious relationships among otherwise uncorrelated measures”. In UX research, this can lead the team to inaccurate conclusions about the users and their experience and can negatively affect design decisions.

Unfortunately, recognising responses of poor quality is not always straightforward. Even when participants respond to a survey randomly, they still produce some non-random patterns in their data, which means that detecting them requires a lot of effort and a combination of various methods (Curran, 2016).

How to check data quality?

A number of techniques have been developed to allow us to check the quality of data obtained in online studies. Some of the most common ones are described below:

Consistency: Measures of internal reliability can indicate inconsistent responses from participants. This is usually achieved by calculating the Chronbach’s alpha score for a questionnaire. Removing participants with inconsistent answers, can improve the internal reliability of a scale. Another way to measure consistency at an individual level is the even-odd consistency score; a separate score is calculated for the odd and even items of a scale for each participant and the relationship between them is examined (within-person correlation). A weak or non-significant correlation suggests poor consistency and could indicate data quality issues.

Speed of responses: This refers to the time it takes for an individual to respond to a number of items, and according to Curran (2016) it is the most widely used tool to eliminate poor quality data. This approach relies on calculating the average time participants spend on specific items (e.g., 2s per item) or on the full survey, and examining outliers (i.e. participants with unusually fast or slow responses).

Accuracy: According to Moss (2019) “correct data are data that accurately measure a construct of interest”. This can be done at a group and at an individual level. At a group level, we examine whether data are related to similar constructs (convergent validity)and not related to dissimilar ones (discriminant validity). For example, learnability scores are expected to be positively related to usability scores. At the individual level, we assess whether people provide consistent responses to similar items. This is one of the reasons questionnaires often have similar questions worded in a different way (e.g., negatively-worded survey items). This allows us to investigate the accuracy of the data by looking at the difference between items measuring the same thing. The smaller the difference, the more accurate the data.

Long-string analysis (response pattern indices): This assesses the number of same answers participants give in sequence (e.g., choosing “I agree” in most statements). According to Schroeder et al. (2021) “…the assumption is that those individuals who are responding carelessly may do so by choosing the same response option to every question”. As a result, long-string analysis can help us remove “some of the worst of the worst responders” (Curran, 2015). You can find more information about how to conduct this analysis in Excel here. It is common to exclude participants who might select the same answer for equal or greater than half the length of the total scale.

Look for outliers: Outliers are data points that differ significantly from other observations. Outliers can have multiple causes and careless responders are one of them (Curran, 2015). Some ways we can detect and deal with outliers are discussed in this article by Santoyo.

Can we improve data quality?

The strategies discussed below can be used before we start data collection.

Include attention checks: Attention checks refer to the inclusion of specific items in questionnaires to check respondents’ attention. According to Curran (2015) when we add these items before we collect data, we can make informed decisions about the data quality by looking at the responses participants give to these specific items. There are many ways to perform attention checks but usually, the researcher identifies a correct response, which indicates that the participant is paying attention to the study. Curran (2015) describes a common technique that:

“…instructs respondents to answer with a particular response option, such as “Please select Moderately Inaccurate for this item”. Individuals who respond with the prompted response are considered correct, and individuals who respond with any other are considered incorrect.”

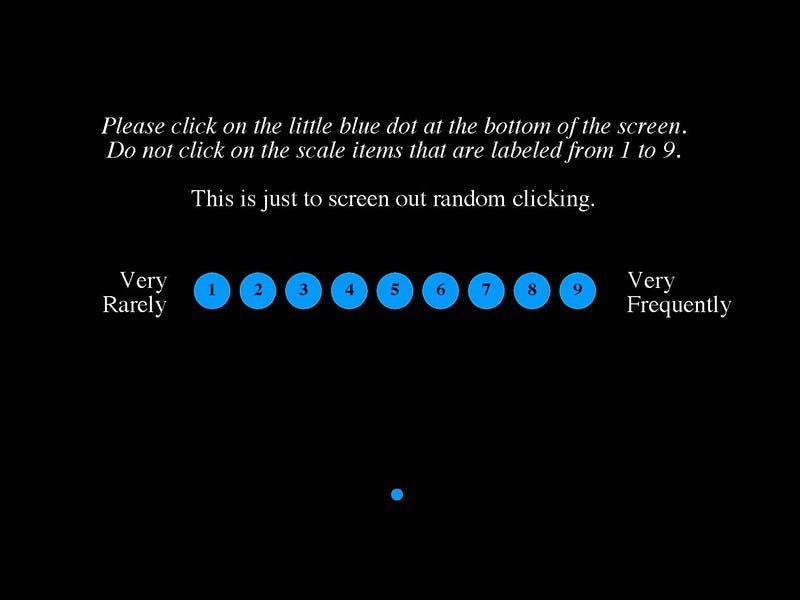

Other forms of attention checks are the inclusion of bogus/infrequency items (e.g., including a random item such as “My main interests are coin collecting and interpretive dancing” in the middle of a survey) and instructional manipulation checks (see figure below).

Bot detection: Poor data quality can sometimes be the result of fake responses coming from spambots and not real people! This can be prevented by using honeypots or CAPTCHAs.

Screen participants: Writing good screening questions can be crucial in any kind of research, including online studies. Multiple articles have been written about this. You can start by this in-depth guide by user interviews.

Seriousness check: This is a very simple measure that was first used by Musch and Klauer (2002). They directly asked their respondents to indicate “the seriousness of their responses”. Even though this approach sounds a bit unusual and simplistic, there is evidence suggesting that it could be useful. For instance, Aust et al. (2013) found that participants who reported higher levels of seriousness answered a number of attitudinal and behavioral questions in a more consistent and predictively valid manner than nonserious participants!

Recruit participants from high-quality panels: There are various ways to recruit participants for research. Not all panels are made equal! Research suggests that there are considerable differences in data quality obtained from different online behavioural research platforms (e.g., MTurk, CloudResearch, Prolific. Qualtrics). For example, respondents who use these sites as their main source of income but only spend a few hours on them per week produce low-quality data.

No technique alone is enough to ensure optimal data quality. For example, recent research has found that relying on attention checks as the sole indication of data quality can have a negative effect on a study and introduce bias.

a person randomly responding to items will not be identified by the LongString variable but may be flagged by other quality indicators. Conversely, a person responding with many 4s in a row may not provide suspect answers, as indicated by an internal consistency measure or outlier analysis, but may be identified by the LongString variable

As a result, the best strategy is to use a combination of methods.

“The strongest use of these methods is to use them in concert; to balance the weaknesses of each technique and not simply eliminate individuals based on benchmarks that the researcher does not fully understand or cannot adequately defend.” — P. G. Curran

Read more

Separating the Shirkers from the Workers? Making Sure Respondents Pay Attention

How to Maintain Data Quality When You Can't See Your Participants

Self-coding: A method to assess semantic validity and bias when coding open-ended responses

Methods for the detection of carelessly invalid responses in survey data

Examination of the validity of instructed response items in identifying careless respondents

Quality control questions on Amazon's Mechanical Turk (MTurk)

It's a Trap! Instructional Manipulation Checks Prompt Systematic Thinking on "Tricky" Tasks

Data Quality of Platforms and Panels for Online Behavioral Research